The NHS launched “test beds” and trials in 2016 and expanded the programme in 2018 to integrate technology, including algorithms and the Internet of Things, into healthcare.

The programme involved partnerships with various businesses, charities and universities, and was funded by NHS England, the Department of Health and the Office for Life Sciences.

Let’s not lose touch…Your Government and Big Tech are actively trying to censor the information reported by The Exposé to serve their own needs. Subscribe to our emails now to make sure you receive the latest uncensored news in your inbox…

The Real Left is publishing a series of essays titled ‘The Health and Social Care Reset for the Big Data Economy’. You can read the first part, ‘The Great Health and Social Care Reset for the Big Data Economy Part 1.1’, which is a timeline of NHS capture during the years 1970s-2013, HERE.

The following is a section of the second part, which is a timeline of NHS capture during the years 2014-2019. We have published the essay in several parts because, totalling a little under 10,500 words, it’s longer than most would read in a single sitting.

The Great Health and Social Care Reset for the Big Data Economy Part 1.2

By Emily Garcia, as published by Real Left on 27 January 2026

Table of Contents

NHS Test Bed and Trials Launched In 2016 And 2018

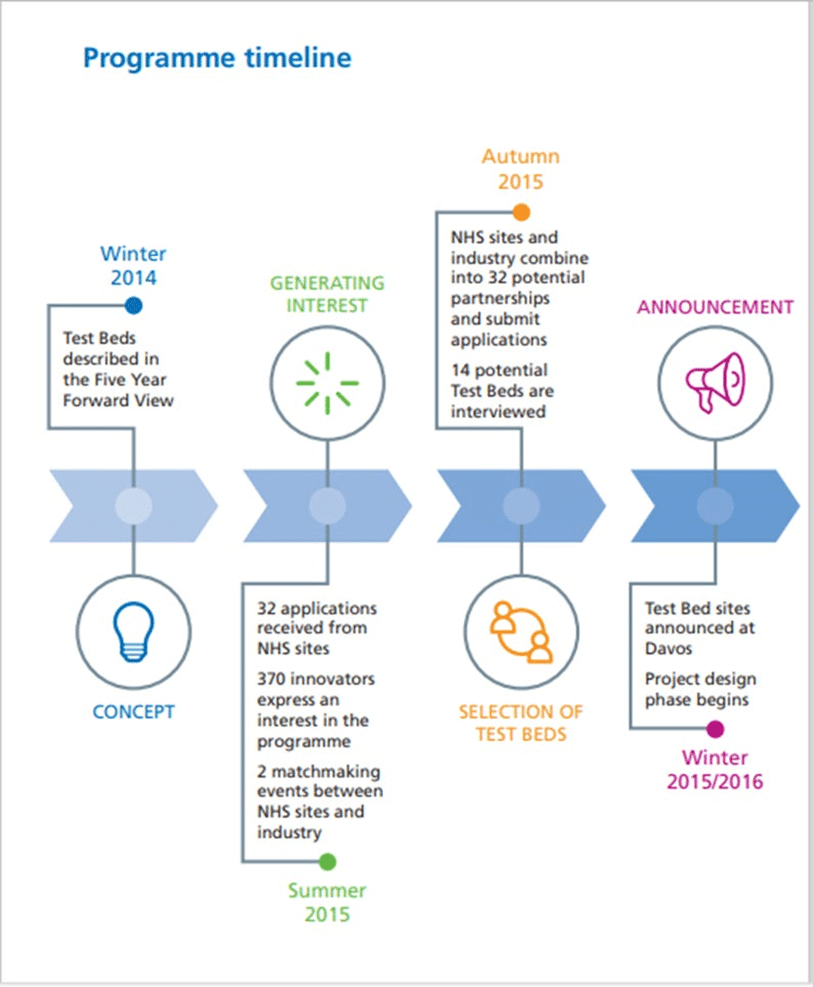

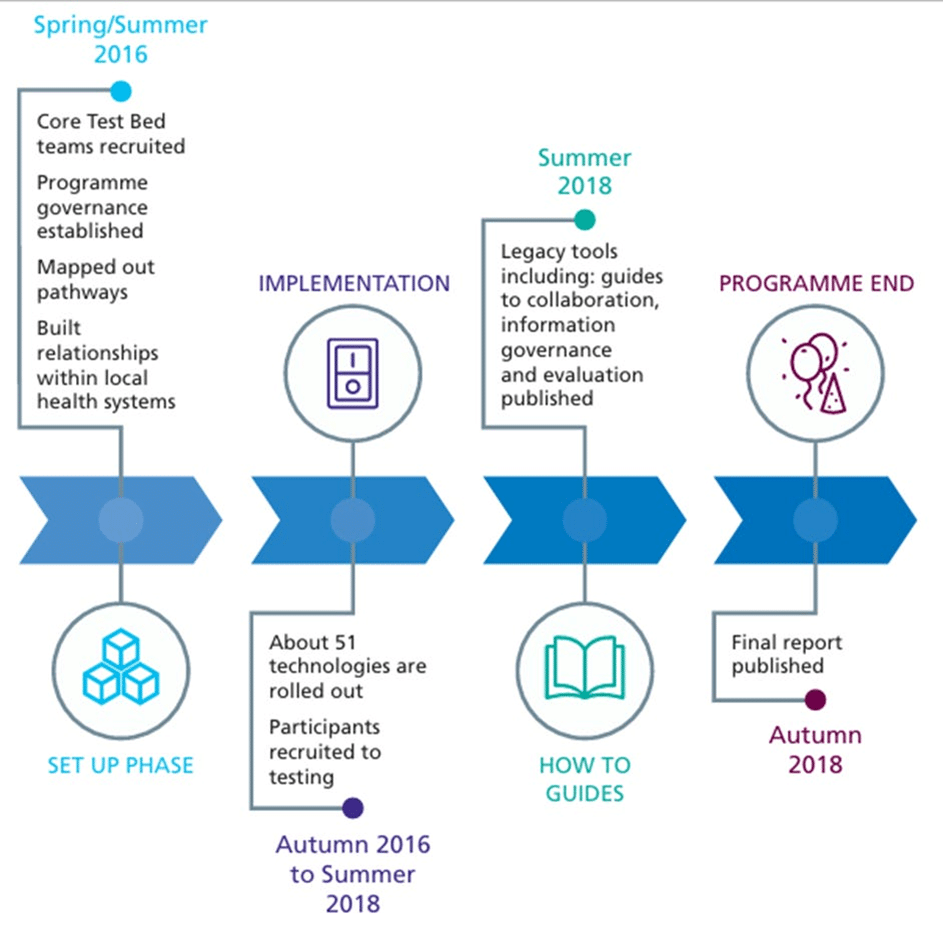

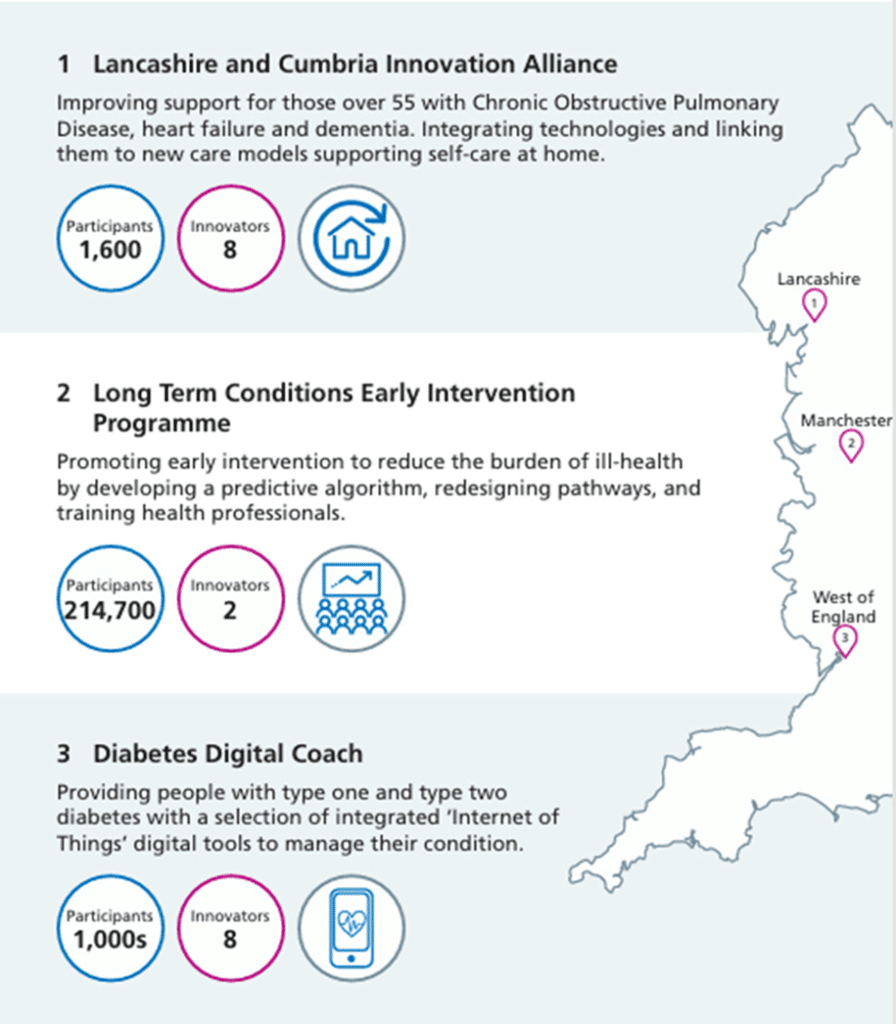

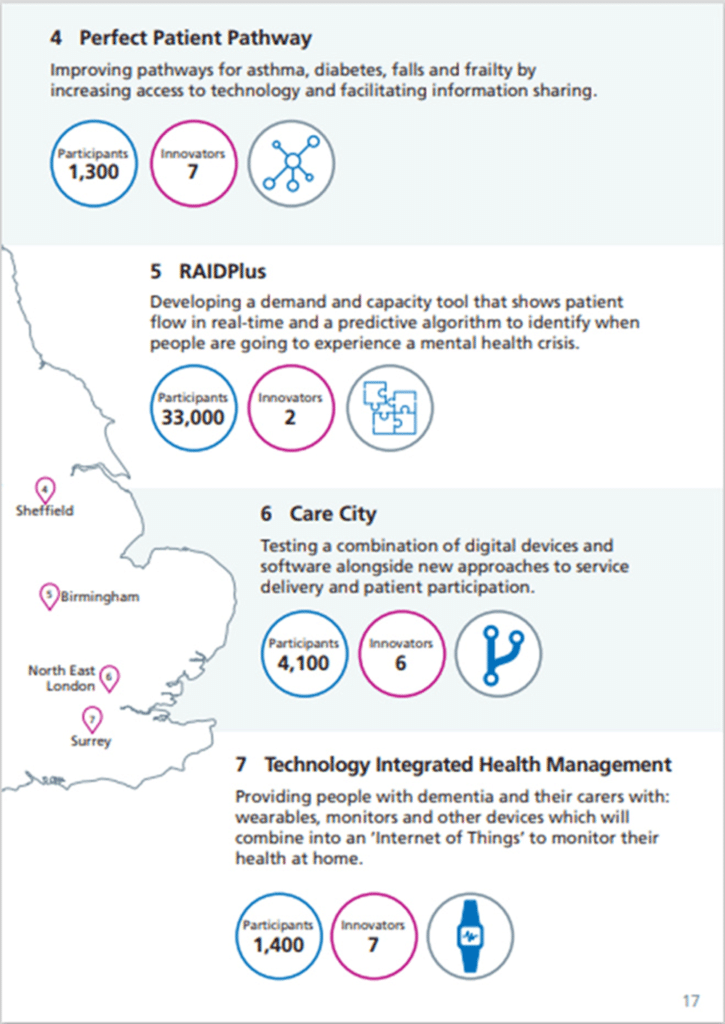

In January 2016, the first wave of NHS test beds, seven separate trials involving an initial cohort of 4,000 patients, was announced at the World Economic Forum Davos meeting: ‘Mastering the Fourth Industrial Revolution’. [122]

The ‘Test Beds at a glance’ infographics in the ‘Test Beds: the story so far’ NHS England report provide a useful overview of these seven test beds, which the report states were designed to tackle clinical challenges “such as dementia, diabetes and mental health through technology including algorithms, sensors and the Internet of Things.”

The programme aimed to generate evidence to “drive the uptake of digital innovations at scale and pace across the health and care system,” and “to harness the potential of digital technologies to support self-management, early diagnosis, prevent unnecessary hospital admissions and bring care closer to home.” [123]

We also learn from the report that the programme is unprecedented in scale, involving “40 innovators, 51 digital products, eight evaluation teams and five voluntary sector organisations,” [124] as well as partnerships with a list of businesses, charities and universities.

It was funded by NHS England, the Department of Health and the Office for Life Sciences. [123] The two, first-wave healthcare-related ‘Internet of Things Test Beds’: Technology Integrated Health Management and Diabetes Digital Coach, were part of the UK government-funded Internet of Things (“IoT”) programme “to support the Internet of Things industry and boost economic growth,” and were managed by Innovate UK. [125]

One of these, the ‘Care City’ trial, connected surveillance technologies such as “GPS trackers, door and electricity monitors, motion sensors, vital sign readers and an avatar” for 24/7 monitoring of dementia patients. If the data identified a significant deviation from baselines, a healthcare professional would receive an alert and decide what type of support to enlist, such as “a call to their carer; a GP appointment; a home visit from the Alzheimer’s Society Dementia Navigator or, if necessary, contacting the emergency services.” [126] One of the stated objectives of the trial was to reduce hospital accident and emergency (“A&E”) admissions in the cohort.

In the Nuffield Trust’s evaluation of the Care City trial, they state that because the trial was classified as a “service evaluation” rather than research, it was not subject to the need for approval from the Health Research Authority (“HRA”) (which would also have required approval from the HRA’s research ethics committee). [127]

Another trial, ‘RAIDPlus’, led by Birmingham and Solihull Mental Health Foundation Trust (with West Midlands police listed as one of the partners), explored a “predictive algorithm, using different data sources, to identify patients who are at greatest risk of experiencing a mental health crisis,” [128] which they term a “risk stratification” approach, [129] in addition to a “demand and capacity dashboard to capture real-time data on patient flow and optimise bed and staff availability.” [130] A RAIDplus mobile app was developed with commercial partner Telefonica. [131]

The ‘Test beds programme: Information Governance: learning from wave 1’ report states that the current legal basis for the use of identifiable information for population segmentation and risk stratification is Section 251 of the NHS Act 2006. [132] However, there was evidently internal doubt over its legality, as the report discloses that the RAIDPlus Test Bed “sought legal opinion regarding the proposed flow of pseudonymised patient data from an NHS Trust to a commercial technology partner.” [133] It is also admitted that “partners within Test Bed sites typically overlooked the increased importance of accessibility and transparency around data processing activity under the General Data Protection Regulation.” [134]

The report also references the test beds’ compliance with the 2018 EU General Data Protection Regulations. However, the health-related exemptions (h) to Article 9 – which concern the processing of personal data revealing racial or ethnic origin, political opinions, religious or philosophical beliefs, trade union membership, sexuality, genetic, biometric or health data – are worryingly broad. They include data “for purposes of management of health and care systems and services,” thanks to amendments successfully lobbied for by the NHS Confederation and the Wellcome Trust. [135]

In October 2018, the Department of Health and Social Care, in partnership with Innovate UK and UK Research and Innovation, announced £7 million funding for a further seven test beds. [136]

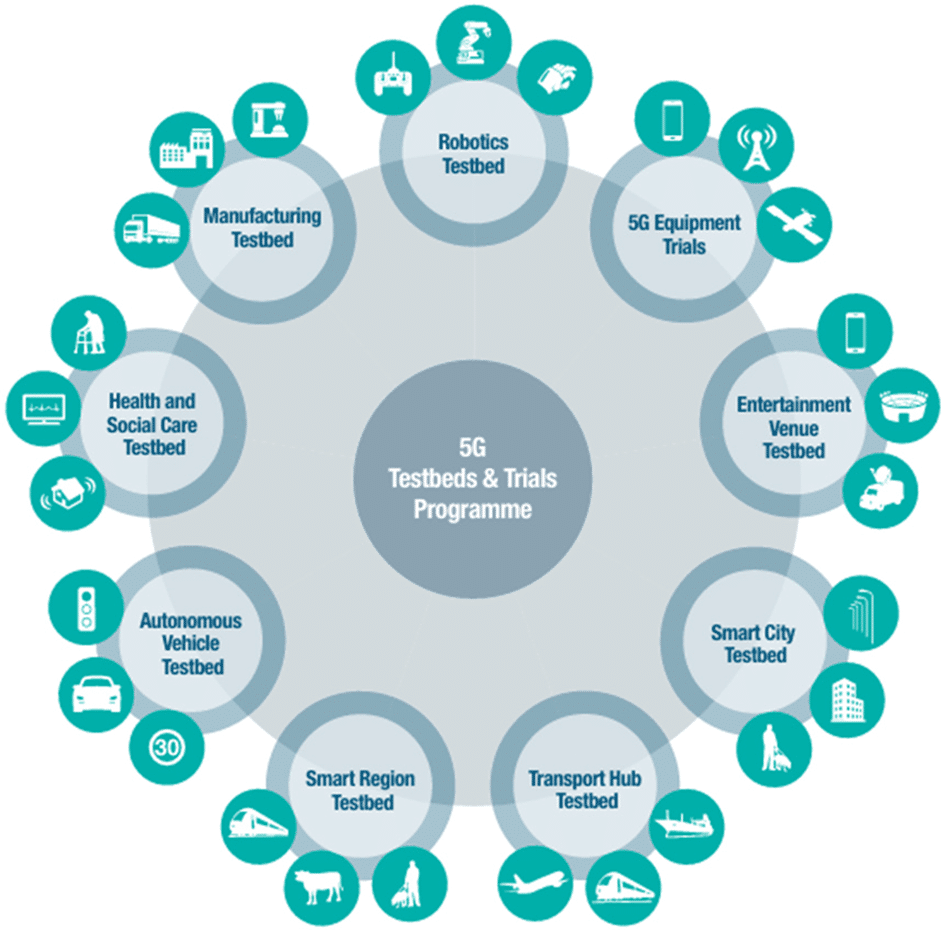

The second wave of NHS test beds occurred in tandem with the launch of the government’s 5G testbed and trial programme, set up to forward the development of 5G services and applications in the UK across multiple sectors. [137]

Liverpool 5G Create: 2018

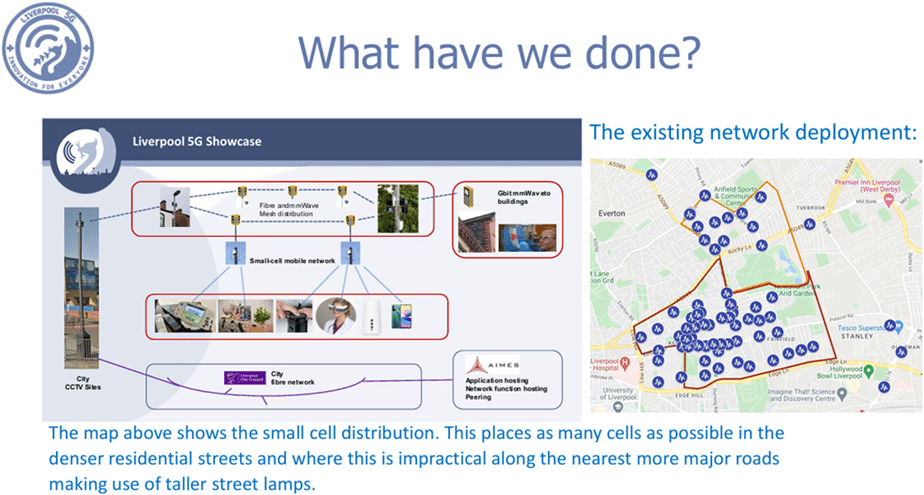

One of these trials was the Liverpool Health and Social Care trial ‘5G Create’, which, from April 2018, established a private 5G mmWave network to support telehealth services for 179 people in the underprivileged community of Kensington, Liverpool. [138]

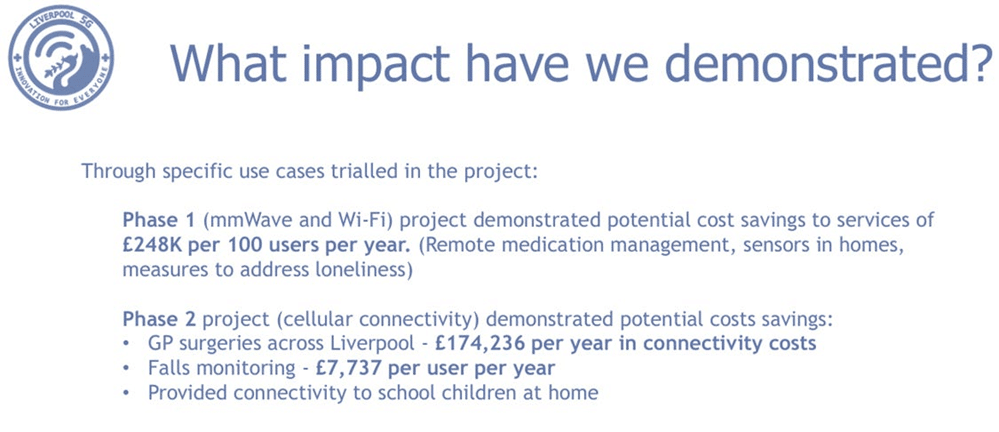

The project was delivered by Liverpool Consortium – a public, private and third sector partnership encompassing the City Council, Liverpool Universities and NHS Trusts, as well as wireless companies – and claimed to be the first 5G supported health trial of its kind in Europe. The consortium was given £4.9 million in government funding to test whether 5G technology “provides measurable health and social care benefits in a digitally deprived neighbourhood.” It claimed projected savings to health and social care services of “over £200k per 100 users per year (dependent on the technologies used).” [132]

The report asks and answers the question, “Why are we doing this?” by explaining how the analogue switch-off in 2025 will render “existing telecare solutions” obsolete and claims that poor access to affordable and reliable (internet) connectivity by Liverpool residents has had isolating impacts.

One trialled case that was mentioned in a government “early impact evaluation” was a “loneliness app” developed by games developer and virtual simulation experts CGA Simulation, [139] which“brings people together to take part in online quizzing, games and chat, to combat loneliness.”

Also trialled was the ‘Haptic Hug vest’, a wearable vest that gives “virtual hugs” by physically reproducing the pressure felt on the chest and back and aims to “help connect isolated older people with family and friends who may live some distance away.” [140]

Some Liverpool residents objected to the technologies being tested, as the government report mentions “large-scale anti-5G protests, which absorbed management resources and capacity,” in addition to stolen equipment; the latter creating delays whilst replacements were obtained. [141]

References

- [122] World Economic Forum. ‘What is the Theme of Davos 2016?’ 16 November 2016. [Online]: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2015/11/what-is-the-theme-of-davos-2016/ (https://archive.is/Jq7TJ)

- [123] NHS England. Test beds programme: information governance – learning from Wave 1. September 2018. [Online]: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/test-beds-programme-information-governance-learning-from-wave-1.pdf p. 1

- [124] Galea, A., Hough, E. and Khan, I. Test beds the story so far. London: NHS England; September 2017. [Online]: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/test-beds-the-story-so-far.pdf p. 8

- [125] Innovate UK. ‘Internet of Things: £1 Million to Support New Hardware.’ Gov.uk; 1 September 2016. [Online]: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/internet-of-things-1-million-to-support-new-hardware (https://archive.is/81oDO)

- [126] Galea, A., Hough, E. and Khan, I. Test beds the story so far. London: NHS England; September 2017. [Online]: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/test-beds-the-story-so-far.pdf p. 24

- [127] Sherlaw-Johnson, C. Evaluation of the Care City NHS England Test Bed: Wave 2. London: Nuffield Trust; 14 June 2019. [Online]: https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/sites/default/files/2019-10/evaluation-protocol-v13-final.pdf p. 29

- [128] NHS England. Test beds programme: information governance – learning from Wave 1. London: NHS England; September 2018. [Online]: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/test-beds-programme-information-governance-learning-from-wave-1.pdf p. 2

- [129] Ibid., p. 7

- [130] Galea, A., Hough, E. and Khan, I. Test beds the story so far. London: NHS England; September 2017. [Online]: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/test-beds-the-story-so-far.pdf p. 22

- [131] The King’s Fund. George Tadros: The RAIDPlus Test Bed Vision. 2017. [Online Video]:

- (Timestamps, 03.15 and 04.36.)

- [132] NHS England. Test beds programme: information governance – learning from Wave 1. London: NHS England; September 2018. [Online]: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/test-beds-programme-information-governance-learning-from-wave-1.pdf p. 7

- [133] Ibid., p. 49

- [134] Ibid., p. 36

- [135] Anderson, R. Online patient records – safety and privacy. 24 April 2013. [Online]: https://view.officeapps.live.com/op/view.aspx?src=https%3A%2F%2Fmedconfidential.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2013%2F04%2FmC_launch_Ross_Anderson_24APR13.pptx&wdOrigin=BROWSELINK Slide 19

- [136] Department of Health and Social Care, Innovate UK and UK Research and Innovation. ‘Faster Access to Treatment and New Technology for 500,000 Patients: The Secretary of State for Health and Social Care has announced £7 million in funding for 2 new programmes.’23 October 2018. [Online]: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/faster-access-to-treatment-and-new-technology-for-500000-patients (https://archive.is/65hlk)

- [137] Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport. UK 5G testbeds and trials. London: The Stationary Office; 2017. [Online]: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/652263/DCMS_5G_Prospectus.pdf p. 16

- [138] Liverpool 5G Ltd. ‘Health and Social Care Testbed.’ 2020. [Online]: https://liverpool5g.org.uk/health-social-care-testbed/ (https://archive.is/ZiEVU)

- [139] Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport. Process and early impact evaluation of the 5G Testbeds and Trials Programme Case Study Annex. London: The Stationery Office; 22 June 2020. [Online]: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/941811/2020-09-30_-_Programme_Initial_Evaluation_-_Case_Study_Annex_-_Final__1___2___1___1_.pdf p. 85

- [140] Beech, L., Porteus, J. The TAPPI inquiry report. Technology for our ageing population: Panel for innovation – phase one. The Dunhill Medical Trust and Housing LIN. October 2021. [Online]: https://thinkhouse.org.uk/site/assets/files/2508/lin1021.pdf p. 50

- [141] Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport. Process and early impact evaluation of the 5G Testbeds and Trials Programme: Case Study Annex. London: The Stationery Office; 22 June 2020. [Online]: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/941811/2020-09-30_-_Programme_Initial_Evaluation_-_Case_Study_Annex_-_Final__1___2___1___1_.pdf p. 83

Featured image taken from ‘NHS75 – History of the NHS’, NHS North East London, 4 July 2023

The Expose Urgently Needs Your Help…

Can you please help to keep the lights on with The Expose’s honest, reliable, powerful and truthful journalism?

Your Government & Big Tech organisations

try to silence & shut down The Expose.

So we need your help to ensure

we can continue to bring you the

facts the mainstream refuses to.

The government does not fund us

to publish lies and propaganda on their

behalf like the Mainstream Media.

Instead, we rely solely on your support. So

please support us in our efforts to bring

you honest, reliable, investigative journalism

today. It’s secure, quick and easy.

Please choose your preferred method below to show your support.

Categories: Breaking News, UK News

Are you looking for an easy and effective way to make money online? Do not search anymore ! e Our platform offers you a complete selection of paid surveys from the best market research companies.

.

Here Come ………………… Tinyurl.com/499zhuvh

Seems the NHS has been wasting a lot of time and a lot of our money to no useful end. It just gets worse and worse – now the worst healthcare system in the developed world.